The Murder Police Podcast

The Murder Police Podcast

The Police Polygraph with Detective Eddie Pearson | Part 1 of 2

Prepare to be captivated as Detective Eddie Pearson of the Lexington Police Department joins us to unravel the truth about polygraph examinations. His tales from the trenches of law enforcement and his stint on the TV show "Relative Justice" will intrigue you, while shedding light on how our body's instinctual reactions can betray our deceptions. Eddie's unique journey—from serving in the military to a transformational career in public service—provides a fascinating backdrop to our discussion on the evolution of lie detection technology.

We also delve into history's curious corners, linking the polygraph to the creator of Wonder Woman and her lasso of truth. The advancements in polygraph technology, such as the groundbreaking introduction of computerization and objective scoring systems, are perplexing and illuminating in equal measure. Discover the meticulous training that underpins Eddie's expertise as a polygraph examiner and how he applies his skills to peel back the layers of human physiology and psychology. This episode is not only an exploration of a misunderstood field but also an homage to those who dedicate their lives to the pursuit of truth.

murderpolicepodcast.com

David's book, True Crime and Consequences is FINALLY available!

This book explores the intricate and often controversial relationship between the true crime community and law enforcement. For amateur sleuths, true crime fans, and social media detectives and cops everywhere.

http://truecrimeconsequences.com/

https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0FBQ4BT5Q

Do you have your copy of David's book True Crime and Consequences? Get your copy today at https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0FBQ4BT5Q.

See what you have been missing on YouTube!

So when that occurs, fight flatter. Freeze is going to kick in, because the only thing I want to do is get away from this snake right. So when that occurs, your blood pressure is probably going to increase, your heart rate is going to increase, your respiratory rate is going to increase.

Wendy Lyons:Warning. The podcast you're about to listen to may contain graphic descriptions of violent assaults, murder and adult language. Listener discretion is advised. The police polygraph with Detective Eddie Pearson, part one of two. Welcome back to the Murder Police podcast. I am Wendy and this is my lovely co-host, David, and today we have with us Detective Eddie Pearson with the Lexington Police Department. Thank you, Eddie, for being here with us.

Eddie Pearson:Thank you for allowing me to be here.

Wendy Lyons:How are you today, Mr David?

David Lyons:Good, I'm excited. I've been thinking about getting Eddie in for a long time because I really want the people out in the audience to get a feel for what a polygraph examination is and what it is, and there's a lot of BS out there. I was just listening to a podcast this week and people got to a polygraph. They had some of it right, but they had a bunch of it wrong. So if people are interested in what these are and what they aren't, today is your day and, eddie, thanks for walking us through it.

Wendy Lyons:Yeah, and, eddie, I hear that you're a pro at this, so I'm so excited. When I saw you pull up and get out of your car, I thought Walter White with Breaking Bad was here to visit us. I was kind of excited, but then I realized that you're just as famous as Walter White on Breaking Bad, so we are really happy to have you.

David Lyons:Well, me too, because I figured this might be you might be honest for a couple of hours, in that Eddie will leave and you'll go back to yourself, probably.

Wendy Lyons:Well, I probably will, because he's already said he can read body language. So I'm like trying to start it to not make eye contact, but then I knew he'd know that I wasn't making eye contact.

David Lyons:Yeah, go ahead and over.

Wendy Lyons:So I really kept staring at him, which he might find really weird as well.

David Lyons:Gotcha. Hey, and speaking of doing the show with this, it's my understanding that you've done a TV show before that actually focused on your role as a polygraph examiner. Tell us a little bit about that and where people can find it.

Eddie Pearson:Yeah, that's right. So it was on a TV show called Relative Justice and we shot I think it was about 300 episodes and it was a court related TV show and I did all the polygraphs for that TV show.

David Lyons:Cool, what was that like Do you give us an idea what a production day would look like?

Eddie Pearson:I usually showed up about four o'clock in the afternoon. They started shooting early in the morning. They would shoot about six to eight episodes per day. So the episodes that I were involved in we scheduled them towards the end of the day because obviously I had to do polygraphs during the day. So I shot most of those in the afternoons or in the early evenings. So most of the episodes I was involved in was the last case of the day. So just basically, I gave a polygraph test the day before. I would send a report to the judge and let her know what the test results were and then I would just go in and testify, just like you would in normal court, and testify about the polygraph results Too cool, how neat.

David Lyons:Yeah, I never knew that. The entire time that we worked together, I didn't know that. One thing, too, is that we'll have a lot of people from various areas watch this. But for the people locally, tell them where these were shot, because that kind of stepped me back a few minutes ago too.

Eddie Pearson:We shot this over in the movie theater on Kodell Drive. So the production company went in and they kind of revamped one of the movie theater rooms and it made it look just like a courtroom. So one room was the actual courtroom where they did the filming. One room was like production make up, the next room is like a green room. So each one of the movie theaters was a different style room and they basically went in and gutted all of them out, except for the one that they shot the TV show in and that they reconstructed an actual courtroom. It's too cool.

David Lyons:A little bit of local history.

Wendy Lyons:Yeah, I never knew that.

David Lyons:That building a laid over there for a while. Again, thanks for coming on board and welcome, and this is going to be a good one for our people that really want to learn.

Wendy Lyons:So Well, why don't you start, Eddie, with Thomas? A little bit about yourself, what you've done prior to now, what you do now Okay.

Eddie Pearson:Well, I graduated high school in Bowling Green, kentucky. I actually joined the Navy while I was in high school. I was 17. I went in the Navy and so I was in the Navy about four to five months before I even graduated high school. After I graduated high school, immediately went off to the Navy, did four years in the Navy. At that time they had a program where you could transfer from the Navy to the Marine Corps or the Marine Corps to the Navy. So I did an interservice exchange from the Navy to the Marine Corps. I was out of the Navy about 30 days and then I was in Paris Island going to boot camp for the Marine Corps, spent about five and a half years in the Marine Corps on active duty.

Eddie Pearson:My last 30 months was on embassy duty. I was assigned to the US Embassy in Port-au-Prince, haiti, and then I was assigned to the US Embassy in Brazil, brazil. So I decided to get out of the Marine Corps, and the Marine Corps at the time had a like a transition program that you had to go through. So what they did is basically taught you interview skills. They taught you how to prepare a resume, things of this nature, to try to prepare you for the civilian world. So what they did because I was stationed at the embassy overseas some of the embassy officers that worked at Langley. They conducted the interviews and it was the mock interview and they taught you how to you know how to dress and how to do an interview and how to submit a resume and how to fill out an application and things like this. So I went ahead and went through everything, went back to Quantico, virginia, because that's where the headquarters for embassy duty was at the time still there. So I got out of the Marine Corps. About two weeks before I got out of the Marine Corps I get a call from a government agency that's in Langley, virginia, and they said we would like for you to go to work for us and I was like absolutely, I will take the job. So I went to work for that government agency as a contract employee, went overseas, I was stationed in Crouton, england, for about four years, decided to come back to the US, took a job in Louisville, kentucky, as a production engineer for an industrial company and I went back into the military reserves.

Eddie Pearson:So I met a friend of mine that was in the reserves, that was a Lexington police officer and he kept trying to get me to take this test for the police department. Now, when I was a kid I never really liked the police, never really thought about being the police. As a kid, every time we played cops and robbers, I always wanted to be the robber, you know, never wanted to be the cop. So I finally went and told him I said, listen, I'll go take this test if you just stop bugging me about it. And he said OK, just take the test. So when I actually took this test at that point it took about 10 months to get on the police department, because you take the test one month, the next month, you take the physical fitness test the next month, and so on and so on and so on. So I took the test and I passed. It kind of went on, did the whole process.

Eddie Pearson:So I get a call from human resources, from the city, and they said you've done well, we want to hire you as a police officer. I said, well, I'm really not interested in it. I got a good job, thanks, but no thanks. He said, well, we're going to hire two classes off this one list. So I will put you on the second list or the second part. So we'll give you a call back in about six months to see if you're still interested in it. I said, ok, thanks, you know, just to kind of get them off the phone. All right, thanks, I'll talk to you in six months.

Eddie Pearson:A couple of days later I'm meeting with the, my boss that I worked for in Louisville, and I told him about this job offer and he said, well, you might want to reconsider that. And I'm like why? What's? What's going on? Are you getting ready to fire me, or you know? He said, well, he had a meeting with the owner of the company and they're getting ready to sell this company to an Indian group and they suspect they're going to take all of our jobs and send them overseas. So I immediately called a lady back human resources. I said, hey, is that job still available? And she said, absolutely, be down here on July the 10th. And I showed up and started a police career Too cool.

Wendy Lyons:How neat, and you're still there.

Eddie Pearson:I'm still there, yes.

Wendy Lyons:Some years later.

Eddie Pearson:Yes, yes, I've been there. Well, I retired in 2015. And so I'm still there now as a civilian, but I still work for the police department.

Wendy Lyons:So before you retired in 2015, were you doing polygraphs then?

Eddie Pearson:Yes, what happened was back in 2005, I actually retired from the military because I did my 20 years and retired out of the reserves and then in 2012, I was assigned to the FBI as a task force officer. So they were going to get rid of the task force at one point. So the chief came to me and said we would like for you to go to polygraph school. And I'm like no, I'm not really interested in polygraph school. I hear the school is extremely difficult academic-wise. It takes like 14 months to get trained. Really not interested. Well, we would really like for you to reconsider this. So I took that as you're going to.

Wendy Lyons:You really need to do this.

Eddie Pearson:Yeah, you're going to polygraph school is the way I took it. So I went to polygraph school in Atlanta. 10-week school, completed polygraph school and then I got assigned to the Kentucky State Police for a year Because in Kentucky you have to do a one-year internship after school. So I finished up, my one-year internship was back at the department and I was the only civilian polygraph examiner we had for about four years and I was assigned to polygraph. So I told the chief. I said you know, I think I'm getting ready to retire. So they converted my sworn detective position into a civilian position and I just feel that civilian position. So I've been there as the polygraph examiner since then.

David Lyons:It would have been a crime to have somebody leave with those skills if the department didn't take a shot, is the place a civilian? And just for people who haven't, if you haven't worked for a chief or a sheriff, they can ask you very nicely on things and you know what the answer is. It's funny when you do that, because we've all been through that at least once, so it's kind of a cultural thing that we can share.

Wendy Lyons:So did you really enjoy polygraphs while you were there the first time before you came back as a civilian?

Eddie Pearson:You know I do enjoy it and it's a good job to have. I think it's a good skill to have because there's a lot of body language and statement analysis along with the polygraph, and probably the best part about it is that I get to assist the detectives in their investigation. So a lot of times when we do give criminal specific polygraphs, we find out a lot more information than we did just on an interview. So I enjoy the polygraph.

David Lyons:Speaking of somebody that did that for a while. It's super valuable.

Eddie Pearson:Yes, very valuable skill.

David Lyons:It's my fact. I think that if they're not used when the time is right, people are missing a huge opportunity. But then again you've got to understand them, and that's what we're here for today, too to get a better grasp of that too, aside from all that work it took to get there, do you have to have like continuing education hours or anything?

Eddie Pearson:Yeah, in the state of Kentucky you have to finish a one-year internship and then you have to take a final comprehensive exam to pass the test. Once you pass the test, then you're actually issued a polygraph license. In the state of Kentucky we are required to have a license and that's controlled through the Justice Department or the Cabinet of Justice here in Kentucky. You have to have a minimum of 20 hours of continuing education every year that is polygraph related, so it can be a polygraph school, an advanced school. It can be interviews and interrogations, language statement analysis. A few years ago they sent us to Roanoke, virginia, to an elicitation school and so we went to that and it was all considered part of the polygraph field. So you have to have those 20 hours every year to maintain your license.

David Lyons:That's a lot of work, a lot of dedication to get to that point too. Well, go ahead and maybe just tell people what is a polygraph, if you want to go into, maybe, the history of it. I've always heard there's a pretty neat story about how Wonder Woman's creator is related. Maybe you can share that. That's a little bit of trivia that people may not know. But go into maybe, what the history of it is, what the equipment's been like over the years and what the equipment looks like now maybe.

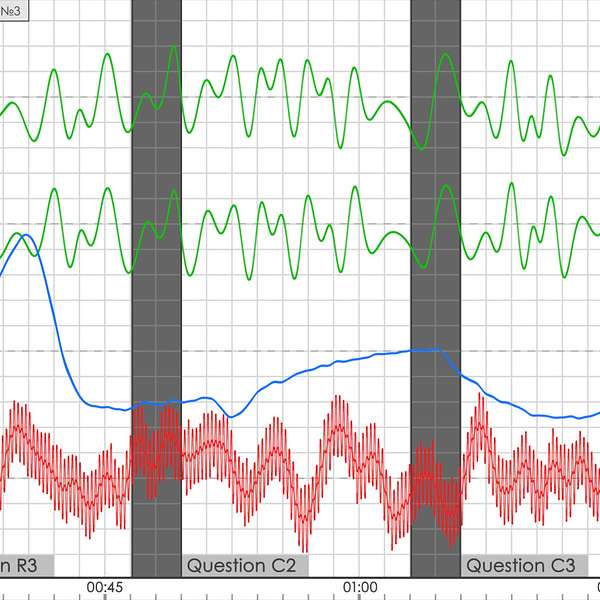

Eddie Pearson:Okay, I don't want to go back too far, but back in the early 1900s there was a doctor by the name of McKenzie and he kind of invented this device called an ink writer polygraph, and what he was doing? He was a medical doctor and what he was doing is he was trying to record irregular heartbeats in people. It was originally designed he designed it as a medical device, so it continued on. The technology continued to improve. In the mid-20s there was a gentleman by the name of John Larson who actually invented what we consider the modern-day polygraph now. He was a medical student and his theory was that anytime you ask or answer a question, you have a physiological reaction in the body to that question, regardless of whether you're telling the truth or where you're telling a lie. And what he did is he said, when those physiological reactions occur, we can use this device called a polygraph and we can monitor your blood pressure, your heart rate, your respiratory patterns, your sweat gland activities, and so what he did is that he created kind of the first polygraph to monitor all this.

Eddie Pearson:So, as they continued on, continued to improve, in the mid-40s there was a gentleman by the name of William Marshton and William Marshton made some improvements to the polygraph. But William's wife was named Elizabeth and Elizabeth came to William and said you know, you need to create a woman superhero, because they didn't have any in the fort. They had Superman, Batman, the Green Lantern, and so he invented Wonder Woman and so he submitted it and Wonder Woman kind of became a superhero. But if you notice, they say that his wife looked a lot like Wonder Woman. Now he said he never modeled it after her. But if you look at pictures of her and you look at pictures of Wonder Woman, they're very close and Wonder Woman has the lasso of truth. Oh, there we go. So it was kind of all tied together.

Eddie Pearson:So polygraph continued on. They made some improvements in the 60s and early 70s with some different techniques and different formulas that we used. So back in 1993, statisticians at the University of Johns Hopkins developed a very sophisticated mathematical algorithm called PolyScore, and PolyScore was a software that you could use on the computerized polygraphs and it will give you the probability of someone being deceptive. So that continued. That's basically in 93s when they jumped into computerized polygraphs. And so we still use PolyScore today and we use another thing called OSS3. Oss3 is objective scoring techniques that we can use. If I'm not mistaken, that was invented by Lafayette Instruments in Lafayette, Indiana. So objective scoring system is what it's called. So we still use some of those skills and some of those algorithms today in the modern polygraphs that we use.

David Lyons:I'm learning like I'm taking it into a fire hose.

Wendy Lyons:I'm just wondering how he remembers all the dates and names Exactly, exactly, most impressed by that.

David Lyons:Yeah, I'll have trouble finding my car when you go out and work Polygraph school.

Eddie Pearson:first week is history. Yeah, exactly, and you got 10 weeks of it, so the first week Wow, neat stuff.

David Lyons:So basically, the advances in the early 90s that you're talking about bringing in statistical data kind of reminds me of Moneyball, you know, with the major league baseball club Big game changer, when people went into using statistics on that too. Well, what about the equipment then? Because I think, when you talk about the last of truth, that there's kind of a neat relative thing on that about how these are done and the equipment and the pieces you have. Just maybe give everybody an overview of what that's like.

Eddie Pearson:All right. Basically, the way it works is you have five components. You have two pneumograph tubes that go around your chest, you have a blood pressure cuff that goes on your arm, you have what's called a PPG or PlasmaGraph it goes on your finger and you have what's called EDAs ElectroDromal Activity. Some of the older examiners call them GSR Galvanic Skin Response. Those are just two plates that go on your fingertips and they just monitor and measure your physiological reactions when you answer questions yes and no.

David Lyons:Got you Pretty cool. So I guess the pneumatic tubes, or maybe. I've always heard that, that last old reference comes in too, too. So you talked about what's being measured for the most part. Is there any details you want to go into as to what those things are?

Eddie Pearson:looking for? Yeah, briefly, I don't want to get too deep into the weeds on it, but basically what happens is that when you're asked a question and you answer the question yes or no you have a physiological reaction in your body. So the way I explain this is this let's say you're walking down the sidewalk and you see a snake run across the sidewalk in front of you. I don't like snakes, I'm not a big fan of snakes. So when that occurs, fight flatter, freeze is going to kick in, because the only thing I want to do is get away from this snake. So when that occurs, your blood pressure is probably going to increase, your heart rate is going to increase, your respiratory rate is going to increase, your galvanic skin response or your electrical dermal activity will increase, your sweat gland activity All that increases because that anxiety goes up and that fight flatter. Fear kicks in and you just want to get away. Well, the exact same thing happens when you answer questions on a polygraph. Not in those large scales, it's a very much smaller reaction, but the same thing happens because your respiratory rate changes. The reason it does that is because the blood from the extremities of your body go to the center portion of your body, around your rib cage, your heart, your lungs, to protect it. That way it causes your sweat gland activity to change and the blood vessels in your fingertips change a little bit because of the lack of blood. So we can see all this on the polygraph instrument as you're answering these questions. So basically, in layman's terms, that's kind of how the physiology works, because fight flatter, fear will kick in. But it kicks in on a much smaller scale because you're just answering yes or no question, because you know if you're lying or you know if you're telling the truth. And we know due to research that lying is a lot more cognitively demanding than telling the truth.

Eddie Pearson:Because when you tell a lie, six things have to occur. The very first thing that occurs is that you have to make a mental decision not to tell the truth. The second thing that happens is you have to decide on what information you're not going to tell the truth about. Third thing that occurs is that you have to construct the lie in your head. The fourth thing that occurs is you have to express the lie. You have to tell the lie. The fifth thing that occurs is that you have to watch the other person's body language to see if they believe your lie. And the last thing is you have to remember the lie. So when you decide not to tell the truth or to conceal information, all six of those things must occur before you tell the lie Exactly. And so that increases the cognitive load in your brain, which makes it much harder to lie because you've got to remember all your lies.

David Lyons:Again, fascinating stuff. The challenge is when people lie, because right now what I'm thinking is here we go much busier than we think we are when we're doing it, which makes it difficult. What are some other tactics you have that indicate that somebody may not be telling the truth? Is there?

Eddie Pearson:something you've tried before. Yeah, I use a lot of body language and I look at a lot of body language when people are talking and I listen to a lot of statement analysis. In my opinion, there's a number of different techniques that you can use, but the easiest way to determine if someone's lying or concealing information is that once you have them tell you the story. Say, for instance, you ask a person, tell me what happened from six o'clock this morning to six o'clock this afternoon, tell me what you did. So they go through their whole day and generally do it chronologically.

Eddie Pearson:I never ask anybody to start at six o'clock. Generally, what I do is I say start where you think is most important, because I don't want to give them a starting point, because where they start is important to me. I want to know where they start their story at. So once I get them locked in, then I start asking them questions about telling me the story backwards, because telling the story backwards is much harder than telling the story forwards, because most people rehearse a lie forward. They will not rehearse it backwards. So when you start asking questions and they start going backwards, generally in my experience what they'll do is they'll give you more detail about their story because they remember it as they're going backwards. But if they got to stop and think about what they said, that's probably an issue. So telling the story backwards is one of my favorite things to figure out what they have left out of the story.

David Lyons:Man, I don't know, it's very genius. Yeah, I don't know, even if I tell you.

Wendy Lyons:I'm just thinking how bad it would be to be as kid or wife. No, exactly, exactly. Don't get any ideas, yeah.

David Lyons:Yeah, just don't get all brainiac, but you know you're right as you were talking, I was sitting here thinking backwards.

Wendy Lyons:what did I do before I got home and I knew I was on the phone with one of my employees and I was sitting there thinking it and then I could play it back forward. But you're right when I was. There are so many details within your day that if you throw an untrue thing there and if you were to ask me about the untruth, I'm going to have to keep lying to make up more stories about that untrue.

Eddie Pearson:And it's much more cognitively demanding to tell the story backwards. Sure, because you really have to think about it. So if you're, telling the story backwards and that cognitive load has dramatically increased. It makes it harder for you to lie, yes, and when you start pausing and start thinking about this and you start, you know, having these start and stop sentences like, I don't remember, you know those. Those are all statement analysis clues that maybe we need to talk about this a little bit more.

David Lyons:Yeah.

Eddie Pearson:And so you just kind of start digging into it and start peeling back that onion that some people say and generally you can, you know, get to what they left out.

David Lyons:Speaking of onions, layers of onions, and some onions are tougher than others. When we're talking about this, this reaction of people have, are there different types of people who respond differently that you have to watch for? Are there some people that that maybe wouldn't respond that way?

Eddie Pearson:And why there are. You know each, each person is is their own individual. You know, I've been in interviews where I've actually shown people a video of them committing the crime and they're like, well, that, somebody who looks like me but that's not me. You know, I mean it happens. So when I do my interviews or I'm doing a polygraph exam, I take each individual person on their own. Everybody's body language is a little bit different. Everybody's statement analysis is a little bit different. Some of it has to do with with cultural. You know where you're from, how you were raised, so you have to take each person independently and adjust as you go, because not everybody's body language or statement analysis is the same and not everybody will respond on a polygraph the same. Now, having said that, let me let me kind of clear this up.

Wendy Lyons:A polygraph exam not only detects deception, it also detects Want to know what that other thing is that a polygraph detects. Well, I guess you got to go listen to the next episode.

David Lyons:The Murder Police podcast is hosted by Wendy and David Lyons and was created to honor the lives of crime victims, so their names are never forgotten. It is produced, recorded and edited by David Lyons. The Murder Police podcast can be found on your favorite Apple or Android podcast platform, as well as at MurderPolicePodcastcom, where you will find show notes, transcripts, information about our presenters and a link to the official Murder Police podcast merch store where you can purchase a huge variety of Murder Police podcast swag. We are also on Facebook, instagram and YouTube, which is closed caption for those that are hearing impaired. Just search for the Murder Police podcast and you will find us. If you have enjoyed this podcast, please subscribe for more and give us five stars in a written review on Apple Podcast or wherever you download your podcast. Make sure you set your player to automatically download new episodes so you get the new ones as soon as they drop, and please tell your friends.

Eddie Pearson:Lock it down, Judy.

Podcasts we love

Check out these other fine podcasts recommended by us, not an algorithm.

The 13th Floor

James York, Alex Cornett, Cece Cornett

The Lexington Podcast

Friis Media

The Speaking of Harvey Podcast

Scott Harvey